California's Life Expectancy Stalls Post-COVID: Experts Raise Alarms Over Lingering Health Impacts

Despite advancements in healthcare access and vaccine distribution, California’s life expectancy has failed to rebound to pre-COVID levels. Experts point to widening health disparities, mental health crises, and socioeconomic stressors as key barriers to recovery.

As the COVID-19 pandemic fades into the rearview mirror for many Americans, public health officials and researchers in California are confronting a sobering reality: life expectancy in the state has not bounced back to pre-pandemic levels. Once a national leader in public health outcomes, California is now facing persistent gaps in longevity that suggest deeper systemic issues—ones the virus merely exposed but did not create. According to recent data released by the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) and corroborated by academic studies from UCLA and Stanford, life expectancy across the state fell sharply during the height of the pandemic and has only made partial gains since.

While the average Californian could expect to live approximately 81 years before COVID-19, current estimates place that number closer to 78. 6—signaling one of the most significant reversals in public health progress in recent memory. The Pandemic’s Initial TollIn 2020 and 2021, the coronavirus killed more than 100,000 Californians.

These deaths alone created a measurable statistical dip in life expectancy. However, what has puzzled many researchers is the plateau that followed. Even with improved treatments, vaccines, and reduced hospitalizations, the recovery in life expectancy has stalled.

Dr. Lina Marquez, an epidemiologist with UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health, says the figures are a ‘canary in the coal mine’ for California’s broader health landscape. “We expected some rebound as vaccines became widespread and acute COVID cases declined,” Marquez explains.

“What we didn’t anticipate was how sticky the damage would be, especially in already vulnerable communities. ”Disparities by Race and IncomeThe pandemic didn’t hit all Californians equally. Black, Latino, and Native American populations in the state saw sharper declines in life expectancy than white or Asian residents.

These disparities persist today, driven by uneven access to healthcare, higher rates of chronic disease, frontline job exposure, and underlying economic stress. In South Los Angeles, for example, average life expectancy in some ZIP codes has dropped to levels not seen since the 1990s. Meanwhile, more affluent neighborhoods in Marin County and Silicon Valley have returned much closer to their pre-pandemic norms.

“It’s not that life expectancy is universally down across California—it’s that some groups are still deeply impacted while others have bounced back,” said Dr. Jerome Collins, a public health researcher at Stanford. “This reflects structural inequities that existed long before the virus.

”Mental Health and 'Deaths of Despair'One underreported factor contributing to stagnant life expectancy is the surge in mental health crises. The last four years have seen alarming increases in suicides, opioid overdoses, and alcohol-related deaths—what some experts call “deaths of despair. ”California recorded over 12,000 opioid-related deaths in 2023 alone, up from fewer than 5,000 in 2017.

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 times stronger than heroin, has become the primary culprit. “People often associate life expectancy changes with diseases like cancer or heart problems,” said Marquez. “But a growing share is now tied to mental health and substance use.

These are silent killers, and they’ve only worsened since the pandemic. ”Healthcare Access: A Double-Edged SwordIronically, California expanded healthcare access more aggressively than most other states, including full-scope Medi-Cal coverage for undocumented immigrants. Yet these gains haven’t translated into longer lives for all.

“There’s a difference between having insurance and actually being healthy,” explains Dr. Collins. “A lot of people still can’t get appointments, face language barriers, or don’t trust the system.

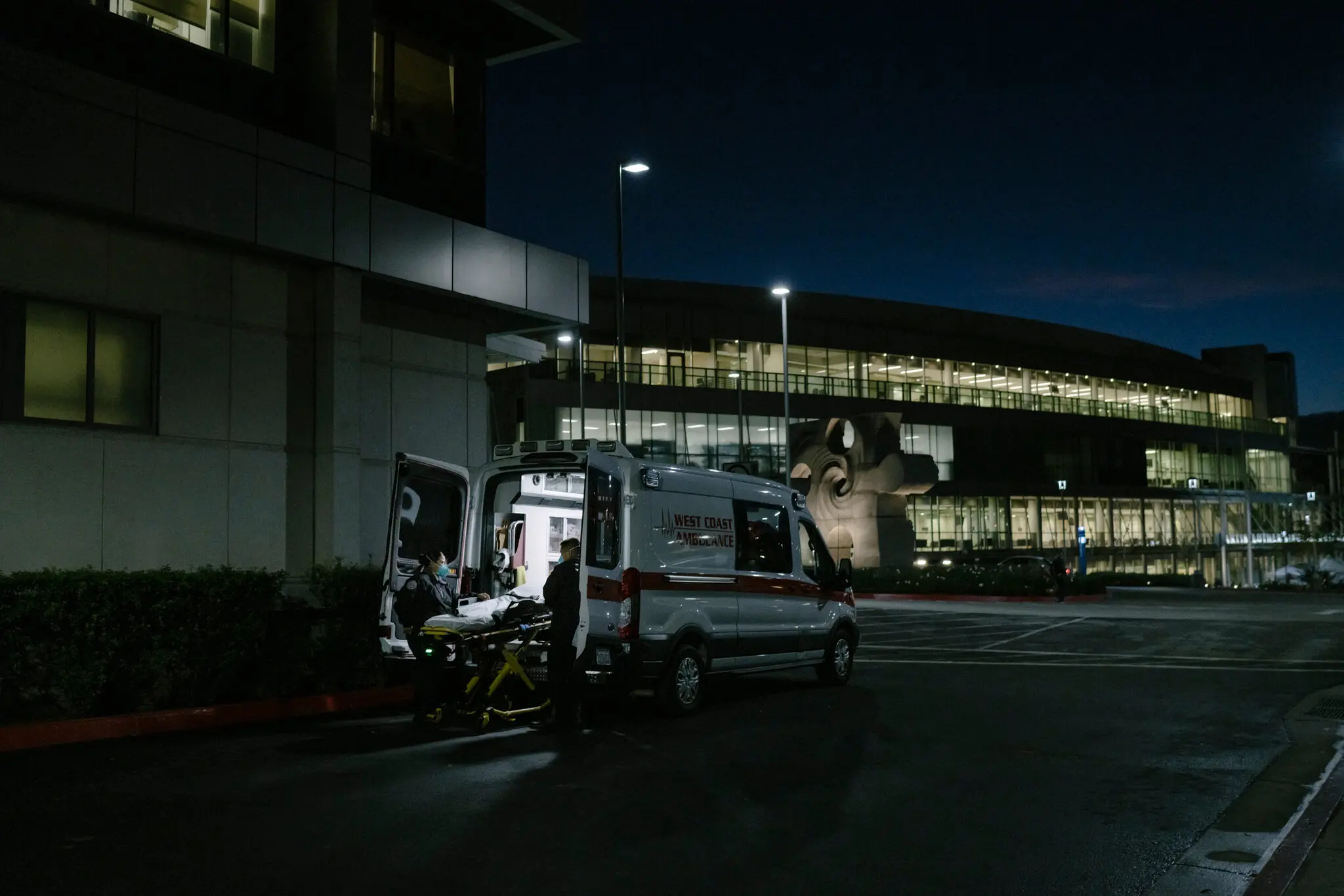

Coverage is the first step—but it’s not the finish line. ”Moreover, the state’s healthcare system remains unevenly distributed. Rural areas and parts of the Central Valley face persistent provider shortages, and urban emergency rooms remain overwhelmed, especially by patients in mental health crises.

Environmental and Economic StressorsIn addition to traditional health metrics, California residents are grappling with stressors that impact longevity in more indirect but equally damaging ways: housing insecurity, wildfires, extreme heat, and inflation. “We’re seeing a rise in stress-related illnesses like hypertension and strokes,” said Dr. Karen Iwasaki, an internal medicine physician in Sacramento.

“Patients are dealing with eviction threats, job loss, food insecurity. It all adds up, and it shortens lives. ”The state’s homelessness crisis, in particular, has become a major contributor to early mortality.

A recent study from UCSF found that unsheltered individuals in San Francisco have a life expectancy nearly 30 years lower than the general population. Long COVID and Chronic ConditionsAnother emerging contributor to stalled life expectancy is the lingering shadow of long COVID. An estimated 5% to 10% of those infected with the virus report ongoing symptoms—ranging from brain fog to heart problems—lasting months or even years.

These symptoms not only degrade quality of life but also exacerbate preexisting conditions like diabetes, asthma, and cardiovascular disease, making long-term recovery harder. Healthcare providers are increasingly sounding the alarm about these patients falling through the cracks. “Long COVID is real, and it’s quietly eroding the health of thousands,” said Dr.

Iwasaki. “But our systems aren’t built to support chronic care at this scale. ”Policy Measures and RoadblocksState leaders have acknowledged the crisis but face political and logistical challenges.

Governor Gavin Newsom has proposed a series of health equity initiatives—including expanded mental health funding, community wellness programs, and infrastructure for telehealth—but experts warn that results may take years. “We’re playing catch-up on a decades-old problem that COVID accelerated,” said Dr. Marquez.

“Quick fixes aren’t going to cut it. ”At the federal level, changes to Medicare, Medicaid, and drug pricing could influence California’s trajectory, but partisanship in Washington has made broad reforms unlikely in the near term. Looking Ahead: A New Definition of RecoveryFor many Californians, the pandemic is over.

Masks are off, schools are open, and travel has resumed. But experts warn that a return to “normal” should not be mistaken for full recovery. “We can’t define success purely by economic growth or mobility data,” said Collins.

“If people are living shorter lives, that’s the ultimate failure of our system. ”Instead, public health advocates are pushing for a more holistic definition of recovery—one that prioritizes longevity, quality of life, and equity across all communities. Conclusion: A Crossroads MomentCalifornia stands at a crossroads.

The pandemic exposed deep cracks in the health and social infrastructure of the nation’s most populous state. Whether life expectancy rebounds—or continues to stagnate—will depend not only on vaccines or policy but on the collective will to confront long-standing inequalities. “This isn’t just a health story,” said Marquez.

“It’s a story about justice, investment, and how we value human life. If we get it right, we can lead the country again. If not, we risk losing a generation to neglect.

”Until then, the numbers remain a haunting reminder that recovery is not guaranteed—and that some Californians are still waiting for it to begin.

23rd july 2025